When it comes to market research, one of the most common — and most misunderstood questions is: What sample size do we need for our results to be representative?

The answer might surprise you: sample size alone doesn’t make a sample representative.

Historic example of a Representative Sample

A historic example of a conducted massive opinion polls among readers of an american magazine to predict U.S. presidential elections failed, predicting the wrong winner, despite conducting 2.4 million interviews. Meanwhile, Gallup, with a sample of just 50,000, accurately forecasted the outcome. Why?

The magazine readers weren’t representative of the general population. They tended to be wealthier and older, skewing the results. Gallup understood something revolutionary: it’s not about the size of the sample, but its composition. By using quotas to mirror the demographics of the broader population, they set the foundation for modern survey research.

Why Does Sample Size Matter?

Sample size still plays an important role — not in making a sample representative, but in determining how precise your results are. Even with a well-composed sample, random variation can cause some results to slightly over- or underestimate the true population values. This randomness is unavoidable, but statistics allow us to estimate the likelihood of such deviations.

Most opinion research relies on a 95% confidence level, meaning there’s a 5% chance the real value falls outside the reported margin of error. For example, if a survey shows 50% market share with a 3% margin of error, there’s a 95% chance the true value lies between 47% and 53%. In fields like pharmaceuticals, where precision is critical, a 99% confidence level may be used.

If you want to reduce that margin of error — and improve precision — there’s only one way to do it: increase the sample size.

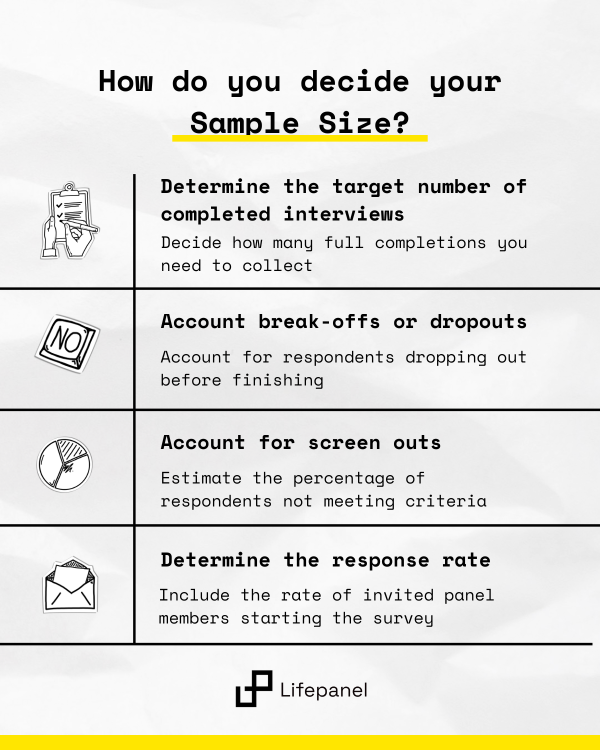

How Do You Decide Your Sample Size?

Determining the right sample is a process that involves working backward from your research goals and accounting for various stages of respondent attrition along the way. The process of calculating sample size typically involves calculations in each stage of the research process.

1. Start with your target number of completed interviews

This is the number of fully completed surveys you need in order to perform your analysis and answer your research questions. It depends on your desired confidence level, margin of error, and how many subgroups you plan to analyze. For instance, if your goal is to measure brand awareness in the general population with a 95% confidence interval and a margin of error of ±3%, you may need around 1,000 completes. This number is your baseline, and everything else in the sampling plan builds on it.

2. Determining break-offs or dropouts

Not everyone who starts your survey will finish it. Some respondents may drop out due to various setups, interests, or technical reasons. These partial responses are called break-offs or dropouts. If you expect, let’s say, a 2% drop-out rate, you’ll need to recruit slightly more participants — in our example, 1,020 — to ensure that 1,000 make it to the end. The break-off rate is often influenced by the design and complexity of the survey, so keeping your questionnaire user-friendly and relevant can help minimize dropouts.

3. Account for screen outs

Screen outs happen when someone starts the survey but doesn’t meet the inclusion criteria defined by your screening questions. For example, if you’re researching smartphone users, someone who doesn’t own a smartphone will be screened out early. The incidence rate — the percentage of people who qualify — helps you estimate this stage. If your incidence rate is 50%, meaning only half the people you invite will qualify, you’ll need about 2,040 people to start the survey in order to ultimately get the 1,020 qualified main interview participants.

4. Determine the response rate

Finally, not everyone you invite will click the survey link in the first place. The response rate reflects how many people actually respond to your invitation. It depends on multiple factors: time of day, day of the week, the relevance of the topic, survey length, incentives, and even seasonal trends. It also reflects the quality and engagement level of your panel. If you expect a 45% response rate, and you need 2,040 people to start the survey, you’ll need to invite around 4,533 panel members to participate.

Each of these steps plays a crucial role in ensuring your sample is not only large enough but also efficient — minimizing waste and maximizing value. By carefully estimating each stage of the funnel, you can avoid surprises in the field and keep your study on track.

How large should your research be?

This brings us to an essential question for any research project: How many interviews do you really need? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, but we can look at a few common scenarios to help guide your decision-making.

Concept Testing

Suppose a company wants to choose between two advertising concepts. The objective is clear: pick the better one. In this case, you don’t need to measure subtle differences—you just need a decisive result. If the preferred concept leads by a comfortable margin, a sample size of around 500 respondents may be enough. That provides a margin of error of approximately ±4.3% at a 95% confidence level. So, as long as the winning concept is ahead by at least 9%, you can move forward with confidence.

Election Research

In election polling, things are rarely that simple when it comes to population size. It’s not just about how much support each party has—it’s also about potential coalitions and who might gain a majority. When party preferences are close and margins matter, even small errors can change the story. If two parties are neck-and-neck and each has a margin of error of ±3%, predictions become highly uncertain. In such cases, increasing the sample size helps narrow the margin of error and improve accuracy.

Subgroup Analysis

Often, researchers want to dig deeper into subgroups within the total random sample. Maybe you’re asking: How do preferences vary by age or gender? The challenge is that analyzing subgroups reduces your base size, which increases the uncertainty around those specific findings. If subgroup insights are important to your study, it makes sense to increase your overall sample size to ensure reliable results across all key segments.

Finding the Right Balance

Ultimately, determining the “right” sample size is a balancing act. It’s about collecting enough data to draw reliable, confident conclusions—without unnecessarily inflating costs, sample size calculators, or timelines. Bigger isn’t always better, and smaller isn’t always riskier. What matters most is that your sample is representative, and your size is fit for purpose.

Lifepanel’s team is here to help you make that call. We can advise you on how large your sample needs to be—based on your goals, your budget, and your timeline—so that your research results are both dependable and efficient.